"The Reimagination of Biblical Events" research presentation by Shelby Craig

"The Reimagination of Biblical Events" research presentation by Shelby Craig

"The Reimagination of Biblical Events" research presentation by Shelby Craig

"The Reimagination of Biblical Events" research presentation by Shelby Craig

"The Reimagination of Biblical Events" research presentation by Shelby Craig

"The Reimagination of Biblical Events" research presentation by Shelby Craig

"The Reimagination of Biblical Events" research presentation by Shelby Craig

"The Reimagination of Biblical Events" research presentation by Shelby Craig

"The Reimagination of Biblical Events" research presentation by Shelby Craig

"The Reimagination of Biblical Events" research presentation by Shelby Craig

"The Reimagination of Biblical Events" research presentation by Shelby Craig

The Reimagination of Biblical Events

Artist’s Biography

Harry Allen Davis, Jr. was born in Hillsboro, Indiana in 1914 to a very religious mother and a minister father. Since his early childhood, Davis dreamed of becoming an artist and was continually supported by his parents who put him through prestigious art schools. Through his raising and education, Davis came to understand art as a tool to improve his community as well as an outlet for sharing his faith. The set of paintings presented here demonstrates both these beliefs quite openly.

After receiving his BFA and going on to study fine art across Europe, Davis returned to America to enlist in World War II as a camouflage artist. After a few years of service, Davis came home, haunted and discouraged by the horrific scenes of violence he had been exposed to. His art began to reflect his new, darkened mindset and the majority of his pieces revolved around emphasizing the gruesome character of the battlefield. However, Davis gradually began to turn from a theme of hopelessness in his art to a theme of redemption, and religious motifs became increasingly present in his work until they became the centerpiece of his compositions. Davis found his religious, optimistic roots once more, and rather than seeing war as a bleak means to an end, he used the grim realities he experienced to show his viewers just how necessary Christian redemption is for the human race.

Each of the five paintings in this exhibition are stunning examples of Davis’s revolutionized mindset. While maintaining the gritty atmosphere of war and employing his knowledge of the European painters he studied under, Davis was able to create five separate scenes which draw on biblical events and which depict humanity as a suffering, desperate race, relieved only by the acts of a loving God. His fascination with classical studies and painters (particularly with famous Greek painter El Greco) mixed with his imaginative portrayals of miracles found in Scripture are a breathtaking combination that truly conveys his heart for religion and for his fellow man.

Exhibition Statement

The five paintings featured in this exhibition each capture the essence of what it is to be human and how the Christian faith fits into that experience. With his work, Harry Davis inspires us to consider the universal and desperate need for redemption while drawing on the style of the world’s greatest classical artists.

Each of the works presented here are detailed and visionary depictions of major events throughout the Bible. Ranging from the account of the Golden Calf all the way through the crucifixion of Christ, Davis skillfully renders the most well-known religious examples of humanity falling short and finding themselves in need of forgiveness. While Jesus Christ and His works are the focal point of most of these paintings, each composition puts the same emphasis on the other figures in the painting who benefit from His ministry. Davis intends for us to relate to these suffering figures and crowds; when looking at these works, the audience can both identify and sympathize with the characters and their emotions. We see the kneeling leper and are inspired to think of a time we relied on Christ for recovery, or we look at the starving crowd desperate for a miracle and consider a time we had no where to turn but God. In this way, Davis uses these paintings as a form of ministry. Without the use of words, they convey to the viewer that he, too, needs the same grace in his life, for he faces the same trials and circumstances as humanity always has.

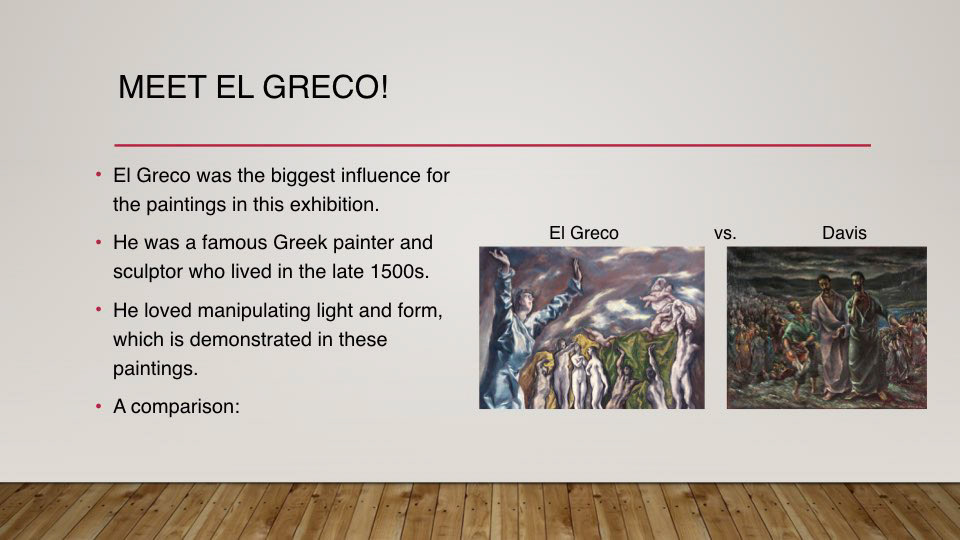

Davis also created these paintings in a somewhat experimental attempt to use the techniques he observed from studying the work of EL Greco. Greco’s main focus was always color—his wild, disproportionate shapes and busy landscapes and scenes were resolved by his expert use of hue and contrast. He felt that themes, feelings, and structure could best be visually explained through color, which resulted in the incredibly dramatic trademark look of his work. As Greco was Davis’s biggest influence for these paintings, the same characteristics can be seen in each of them. Where proportion, realism, and an abundance of events within a small scene add chaos, Davis’s use of color, lighting, and emphasis remedies the images by adding coherence and meaning.

This fierce combination of an unflinching reality and a delicate, playful art style results in a composition as beautiful as it is profound. Davis’s imitation of classical art takes on a modernized and beautiful form of ministry almost as effective as the stories pictured within them.

Piece Descriptions:

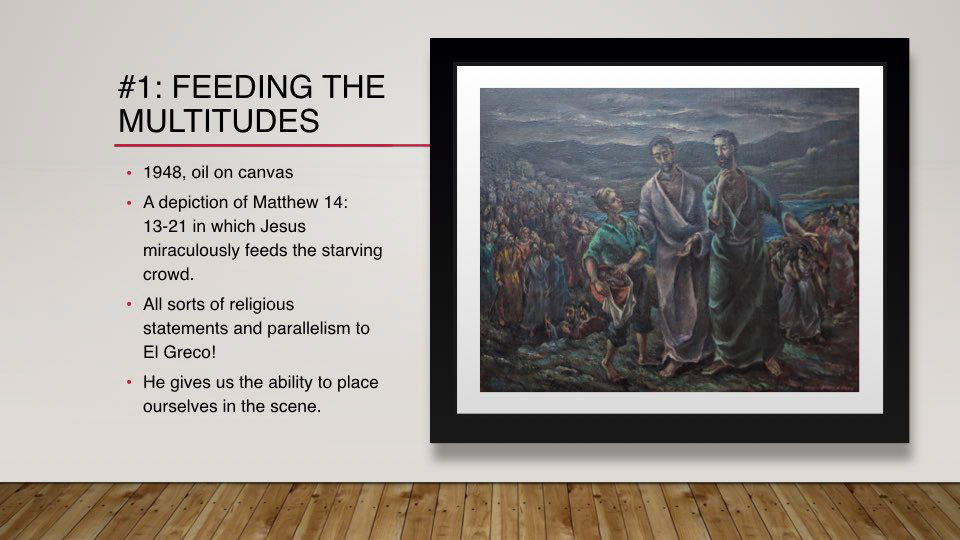

In Feeding the Multitudes, Jesus is posed as a servant while enduring the company on either side of Him. The young boy holding the basket of loaves and fish expects a miracle, as many of the crowd who followed Jesus would have. He stares at Jesus with imploring eyes and removes the sheet from the basket, silently asking Him to perform his miraculous work on it, while the crowd of 5,000 waits boisterously in the background. Jesus acknowledges the child, holding out His hands in a presentation of servitude and peace, able and willing to comply and feed the bustling crowd. Thomas stands on the opposite side of Jesus, doubtfully eyeing the basket of food and waiting hesitantly to see whether or not Jesus really can pull off what He claims to be able to. Although their poses and expressions are polar opposites, the theme of the paintings revolves around those waiting on the salvation of Christ—Thomas, the young boy, and the crowd. Everyone pictured looks to Jesus to act and give them what they desperately need, whether they faithfully believe He can do so or not. And regardless, Jesus obliges them. El Greco’s influence can be seen in the distinction between the foreground and background, as well as the vibrant use of color. Jesus dons a long white robe, causing him to stand out and become the centerpiece of a largely cool-colored and darkened image.

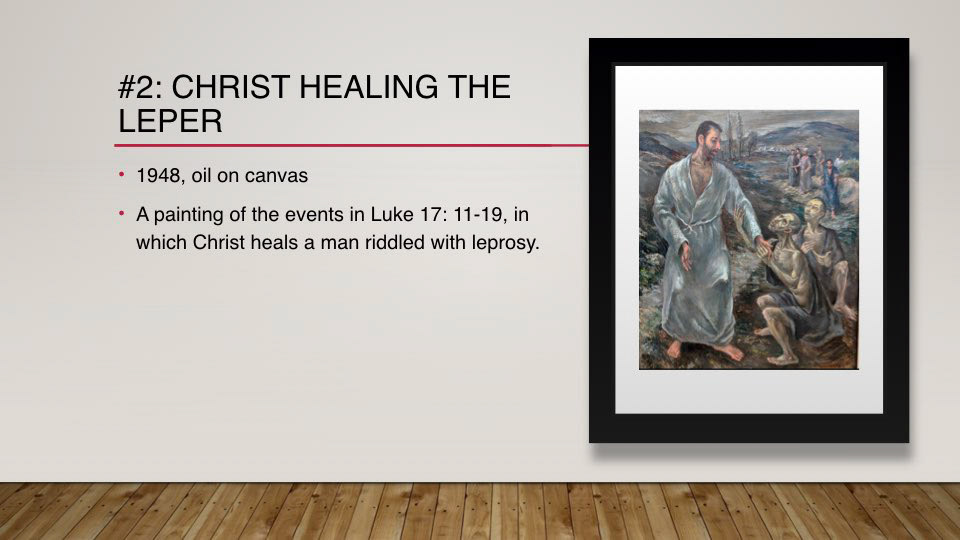

Christ Healing the Leper is another, more straightforward example of the pure compassion and love that drove Jesus’s ministry. Once again, several elements of El Greco are utilized here to draw the viewer’s eye to the healing of the Leper. Jesus’s being clad in His usual white robe and his height, which towers above everyone and everything else in the painting, immediately make Him the forefront of the action taking place. The eye then travels down over His arm, linked with the kneeling leper’s, who desperately holds on to him, begging for His miraculous healing. The horrifying appearance of the lepers themselves is a testament to how unsightly they were and how dangerous they would’ve been to come into contact with, and yet Jesus unreluctantly holds the leper’s hand and stares down directly into His eyes, acknowledging him as a person and not a monster. Again, His hands are spread in a universal gesture of compassion. The small crowd of priests in the background comes forth to witness the healing with awe on their faces and in their body language.

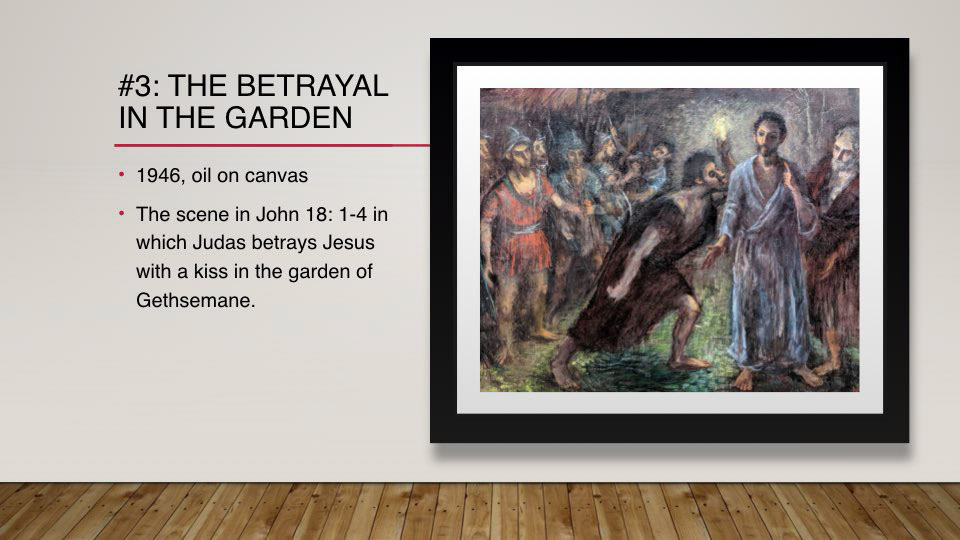

The Betrayal in the Garden sees some different dynamics between Jesus and the crowd, but Jesus relays the same message as He does in the other works. It’s the depiction of the moment of Judas’s betrayal in the Garden of Gethsemane while the soldiers wait in the background. Some of the same elements are repeated: again, Jesus is clad in His holy white robe, and again, He is the larger-than-life figure of the composition, taller than anyone surrounding Him. And, once more, He holds out one upturned palm in a gesture of surrender and peace. His body language clearly shows His acceptance of His fate without a fight, and He even points to Himself to illustrate His answer to the soldiers’ question: “I am He.” Judas, with his posture leaning in toward Jesus and his lips pursed, is in the middle of the kiss of betrayal, and his stance leads the eye of the viewer smoothly through each interaction in the painting. On Jesus’s other side stands Peter, whose facial expression portrays his conflicted thoughts flawlessly; his stance is ready to defend Jesus, but his eyebrows are drawn together and his countenance hints at the doubt which would soon lead him to deny knowing Jesus at all. Finally, aside from Jesus’s disproportionate height and the dramatic coloring and poses, another tribute to El Greco can be seen here. The light source, a lantern held up behind Jesus and Judas’s interaction, is a subtle nod to a similar scene setup in Greco’s version of the betrayal.

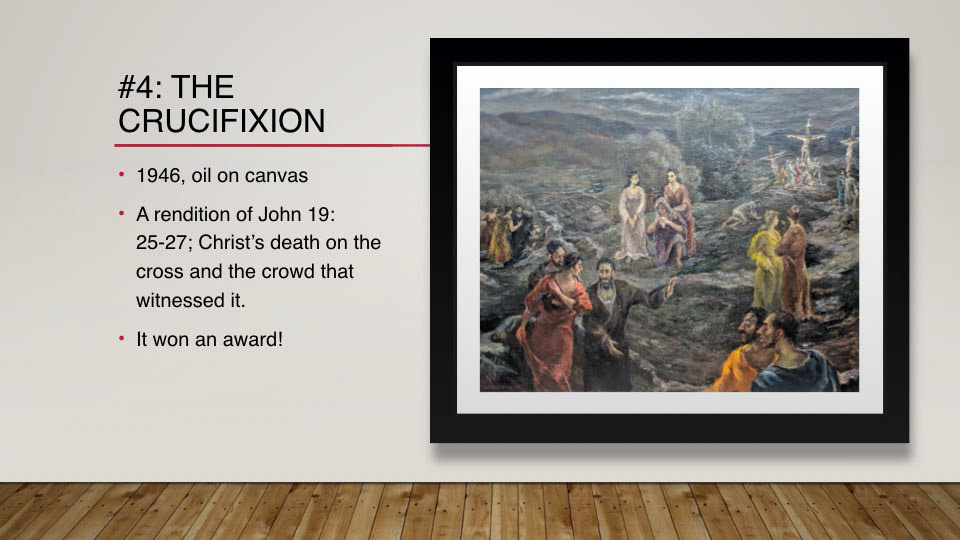

Davis’s portrayal of The Crucifixion is an incredibly unconventional one—Jesus’s body, hung on the cross, is nowhere near the center of the painting. On the contrary, it’s sat far back in the corner, almost unnoticeable, while the painting favors the confused and mourning groups scattered throughout the forefront of the composition. The focus isn’t on the event of the crucifixion, it’s on everything that took place immediately afterwards and the chaos and sadness that ensued. Every single aspect of this painting is meant to reflect the disorientation that resulted from Jesus’s death. The ground and the sky are grey and muddled together, and the groups clothed in all different hues with different reactions and different placements in the paintings add to the chaos. In the center, we see Jesus’s mother kneeling and weeping, absolutely desolate, but in the foreground there are several people who were simply bystanders and look baffled more than anything. The only common denominator here is a general uncertainty as to what will happen next, and if this truly was the end of the dynamic and explosive ministry of Christ. Rather than demonstrating the active love of Jesus and His ministry, as in the other paintings, Davis uses this scene of the Crucifixion to show us how meaningful Jesus’s ministry was, and the incredible effect His love and words had on those who followed Him.

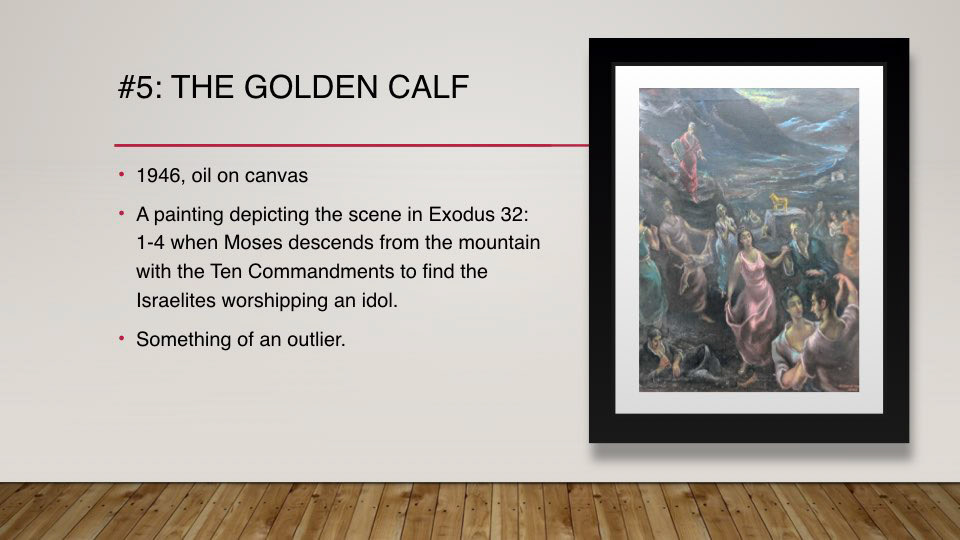

The Golden Calfstands out in this group of paintings because it’s the only one that doesn’t center around Jesus and His ministry. Despite this, it does maintain the ongoing use of drama, intense lighting, and the generally beautiful layout of a hectic but iconic Biblical story. In The Golden Calf, Davis paints the scene of Moses descending from the mountain with the Ten Commandments and stumbling upon the debauchery taking place at the foot of it. Similar to Davis’s The Crucifixion, the holy figure of Moses is set in the background, and the composition is centered more on the salacious behavior up front. The two dancers in the bottom right corner set a strange angle full of movement for the rest of the image, and although it’s placed far in the background, the Golden Calf itself is highlighted by the light coming down from God’s presence. But unlike The Crucifixion, Moses is the focal point of this painting, despite his placement. The bright light radiating from the mountain highlights Moses, walking in an amazed stupor, back to the scene before him. This painting does a magnificent job at illustrating the contrast of worldly living versus living according to God. The dark colors and chaotic poses of everyone on the ground is totally earthy; they’re drunk, confused, and practice lust and seduction, while Moses’s face portrays his reward for his faithfulness to God. He’s been gifted with the Ten Commandments and a direct interaction with his God, and the pure, bright light on him contrasted against the muddled colors of everyone else is symbolic of this difference.

Researcher’s Bio:

Shelby Craig is a senior with an Art and Design major and an emphasis in Art History at Asbury University. Her academic career has centered on work and research in various galleries in Lexington, Wilmore, and France, as well as the creation of her own art. She hopes to one day work for a major acclaimed museum and loves being around classical art almost as much as she loves her pet fish, Merle Haggard, and making little clay sculptures in her free time. She has curated this show on the American art of Harry Allen Davis, all of which was created during the 1940s and displays traditional American and religious themes.